Tropicalia antropophagous design

Tropicália was an art movement that opposed the military regime that controlled Brazil between 1964 and 1985. In 1964, a CIA-backed military xtagroup brought down the elected government of President João Goulart. By 1968, the military crackdown on dissent was devastating to Brazil as a whole and specifically for artists: it led to an era deemed the “vazio cultural” (“cultural void”). Tropicalia emerged during this period as a counterpoint to the prevailing style of the military dictatorship. A scrappy, distinctly Brazilian take on pop art, it informed every medium from rock music to posters, seeking to redefine the country’s culture, let down by modernity.

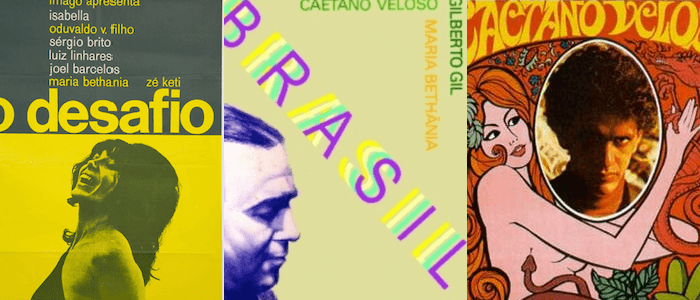

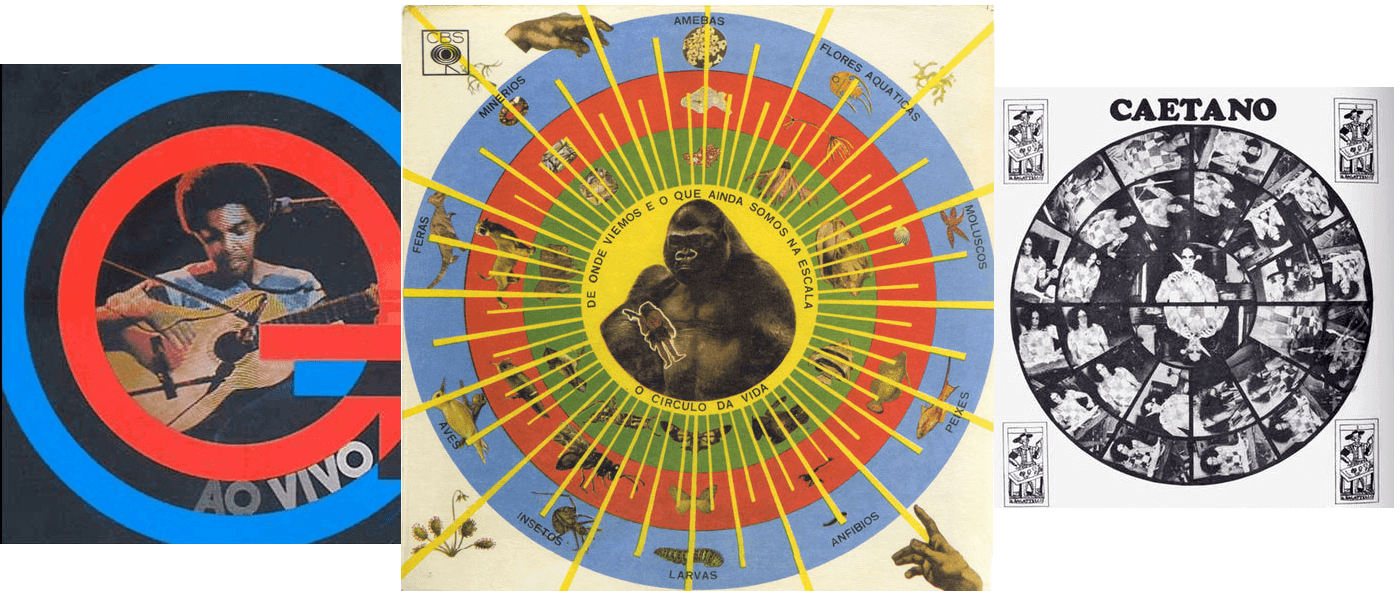

Tropicalia emerged as a new, alternative aesthetic to the predominance of modernism (Cardoso 2008, p. 200). It’s core was the concept of “visual antropophagy” — the ingestion and re-appropiation of international cultural elements to incorporate them and adapt them to the Brazilian context (Espinosa 2018). In this sense, it consisted of a mixture of eclectic elements: technical and sophisticated kitsch, the visual pollution of American pop art, the sinus lines of Art Nouveau, symmetrical layouts and sans-serif types inspired by the Ulm school and the fine rules of German layout (Longo 2016, Espinosa 2018). More than anything, it was a contrasting locus of reality and fantasy, as well as the contrast of tradition and innovation (Tafarelo de Oliveira 2011). In the face of the lack of formal design rules of the movement, a philosophy of ingestion was followed in the design of this theme.

Key Characteristics

The main characteristics of this theme were:

Music

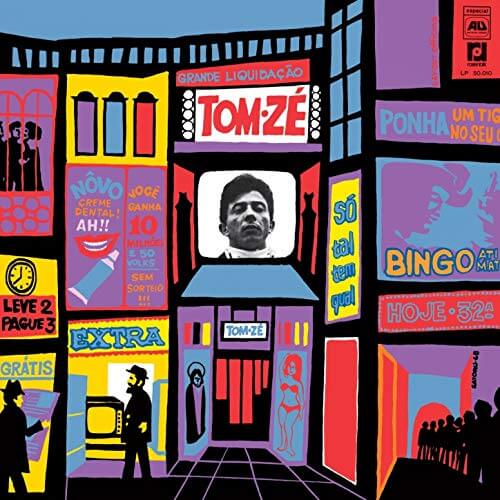

Tropicalia was, above all, Brazil's defiant soundtrack in the late ’60s and early ’70s. The scene was encompassed by a bold and adventurous take on Brazilian pop music. Crucial names include Caetano Veloso, Gilberto Gil, and Gal Costa, as well as Tom Zé and Os Mutantes. The combination of adventurous rock’n’roll and avant-garde sounds with the native rhythms of Brazil is why the theme includes-- perhaps surpring and even discomforting at first--audio. The song that is played is Quero Sambar Meu Bem by Tom Zé.

The audio file was implemented in the JavaScript file, as part of the switchTheme(input) function which initializes Tropicalia when selected by the user:

var sounds = document.getElementsByTagName('audio');

for(i=0; i<sounds.length; i++) sounds[i].pause();

if (input.name == "themes/tropicalia") {

var audioElement = document.createElement('audio');

document.head.appendChild(audioElement);

audioElement.setAttribute('src', '../audio/tropicalia/Sambar.mp3');

audioElement.play();

};

Antropophagic Typography

The anthropophagous nature of the movement is evident in its eclectic typography. A mixture of sans-serif, minimalist typefaces were mixed with psychedelic and pop-art influenced ones, as well as ones resembling the local culture. This is why in the tropical design you can find a mix of sans-serif typefaces (Yoxall, Tex Gyre Adventor, Ostrich Sans, and Boomtown Deco), psychedelic ones (Dogsmoke, Beamie), and distinctly Brazilian ones (Tropicalia, Milho). To give the viewer an anthropophagi mood since the beginning, she is first presented with the three main titles of the document in a mix of psychedelic and sans-serif typefaces.

The open fonts were imported as local files:

/* beamie */

@font-face {

font-family: beamie;

src: url("../../fonts/tropicalia/beamie.ttf") format("opentype");

}

/* boomtown-deco */

@font-face {

font-family: boomtown-deco;

src: url("../../fonts/tropicalia/Boomtown-deco.otf") format("opentype");

}

/********DOGSMOKE********/

/* dogsmoke */

@font-face {

font-family: dogsmoke;

src: url("../../fonts/tropicalia/Dogsmoke.ttf") format("opentype");

}

/* dogsmoke-ii */

@font-face {

font-family: dogsmoke-ii;

src: url("../../fonts/tropicalia/Dogsmoke-II.ttf") format("opentype");

}

/* dogsmoke-thunder-ii */

@font-face {

font-family: dogsmoke-thunder-ii;

src: url("../../fonts/tropicalia/Dogsmoke-Thunder-II.ttf") format("opentype");

}

/* dogsmoke-thunder */

@font-face {

font-family: dogsmoke-thunder;

src: url("../../fonts/tropicalia/Dogsmoke-Thunder.ttf") format("opentype");

}

/* dogsmoke-ii */

@font-face {

font-family: dogsmoke-ii;

src: url("../../fonts/tropicalia/Dogsmoke-II.ttf") format("opentype");

}

/********DOGSMOKE********/

/* milho */

@font-face {

font-family: milho;

src: url("../../fonts/tropicalia/Milho-Cozido.ttf") format("opentype");

}

/* ostrichsans */

@font-face {

font-family: ostrichsans;

src: url("../../fonts/tropicalia/ostrichsans-medium-webfont.ttf") format("opentype");

}

/* tropicalia */

@font-face {

font-family: tropicalia;

src: url("../../fonts/tropicalia/Tropicalia-Brush.ttf") format("opentype");

}

/********TEXGYREADVENTOR********/

/* texgyreadventor-italic */

@font-face {

font-family: texgyreadventor-italic;

src: url("../../fonts/tropicalia/texgyreadventor-italic.otf") format("opentype");

}

/* texgyreadventor-bolditalic */

@font-face {

font-family: texgyreadventor-bolditalic;

src: url("../../fonts/tropicalia/texgyreadventor-bolditalic.otf") format("opentype");

}

/* texgyreadventor-bold */

@font-face {

font-family: texgyreadventor-bold;

src: url("../../fonts/tropicalia/texgyreadventor-bold.otf") format("opentype");

}

/* texgyreadventor-regular */

@font-face {

font-family: texgyreadventor-regular;

src: url("../../fonts/tropicalia/texgyreadventor-regular.otf") format("opentype");

}

/********TEXGYREADVENTOR********/

/* yoxall */

@font-face {

font-family: yoxall;

src: url("../../fonts/tropicalia/Yoxall.ttf") format("opentype");

}

And were applied to each of the core structural elements of the HTML document:

body {

font-family: "yoxall";

}

h1 {

font-family: "dogsmoke";

}

h2 {

font-family: 'yoxall', sans-serif;

}

h3 {

font-family: 'beamie';

}

Psychedelic Influence

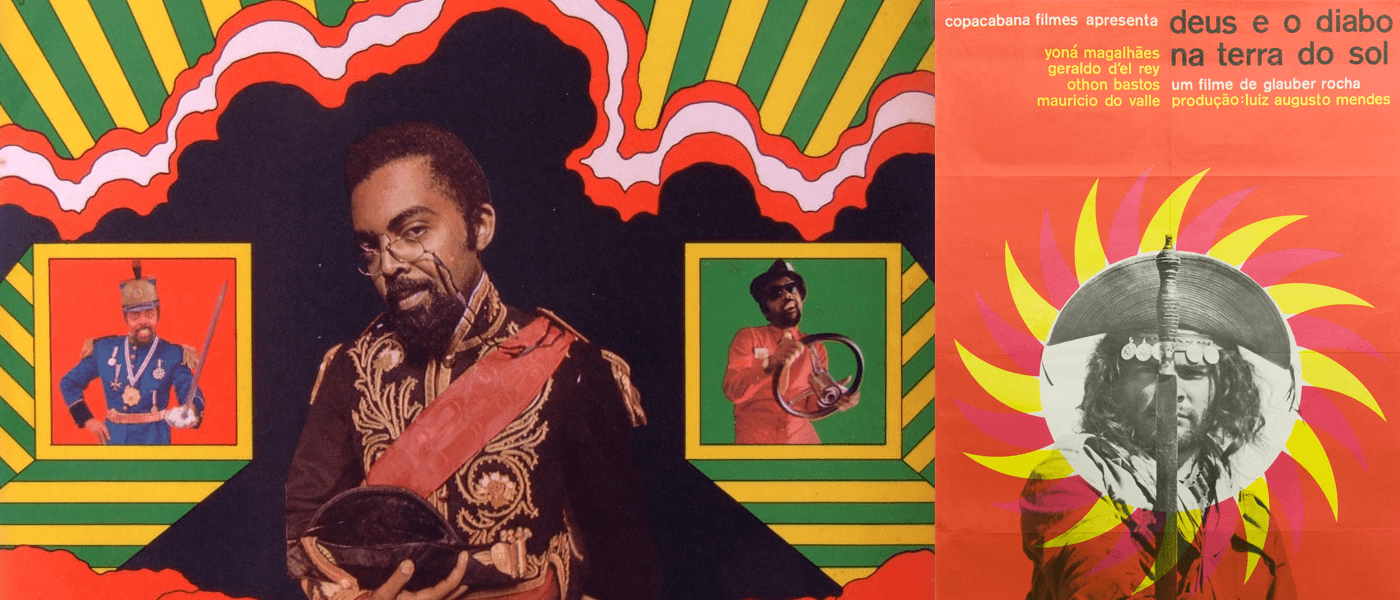

This theme is inspired by the psychedelic and pop-art elements ingested by the Tropicalia movement. Duarte used "psychedelic features through illustration [to] refer to a dreamlike atmosphere” (Tafarelo de Oliveira 2011). While most of the objects from that time were printed and thus had no real animations, the concept behind (hallucinations, distortions of perception and awareness, abstraction and confusion) is captured by the theme’s use of animation. The initial animations create a sense of disorientation in the user, and fulfill the psychedelic goal of making letters look like they are moving.

You can also see psychedelic influence in the background chosen for the h4 (section title) elements, which employ an animation created by samurai (credited in the CSS code as well).

Another example of these effects is the theme’s styling of images. The images were styled according the the movement’s predilection for circled images with pop-art and psychedelic styled elements. This is why the images in the theme were circled, have a border as seen on multiple source images, and also have a hover effect (only on desktop screens) that provides a disorienting animation.

The initial animations were created by simply using CSS transform, in different ways for small and large screens:

Small Screens

h1 {

transform: rotate(180deg);

transition: transform 3s ease-in-out 2.9s;

}

h3 {

transform: scale(1.5) translate(25vw);

transition: transform 5s ease-in-out 5s;

}

Large Screens

h1 {

transform: rotate(-180deg);

transition: transform 5s ease-in-out 2.9s;

}

h1:hover {

transform: rotate(0deg);

transition: transform 2s ease;

}

h3 {

transform: rotate(-180deg);

transition: transform 5s ease-in-out 2.9s, color 5s linear 1s;

}

h3:hover {

transform: rotate(0deg);

transition: transform 2s ease;

}

The samurai psychedelic background works as follows:

@keyframes cells {

from { background-size: 22px 22px; }

to { background-size: 24px 24px; }

}

h4 {

animation: cells 0.4s linear infinite;

background-image: repeating-radial-gradient(#A9A355 8px, white 12px);

}

This is the code that makes the image round, creates two shadows to make them look like a 3D border, and makes the colors rotate as a gradient through the color wheel:

figure > img {

border-radius: 50%;

box-shadow: -1vw 1vw 0 1vw black, 1vw 0 0 3vw #e0d289;

animation: colorRotate 10s infinite;

}

figure > img:hover {

transform: rotate(1080deg);

transition: transform 3s ease-in;

}

Daring and Complementary Colors

The Tropicalia design bid farewell to the achromatic tones that design schools taught at the time (Cuzner). Instead, the designs used “daring” colors. Especially green, yellow and red shades were popular, as the colors represented a "green-and-yellow Brazil stained with blood, metaphorized in a cynical and debauched layer" (Rodrigues, 2008, page 207, translation mine). This choice of colors represents a relation with dictatorial violence and the historical facts of the time. This is also what influenced the choice to have a black border on desktop, as seen in some of the source images.

One of the most relevant color combinations for the pieces is the complementary contrast (a combination of colors that are in opposition of 180 ° in the chromatic circle). This was the direct inspiration for the choice of the color for highlight and linked text (#9B62AB), as it is the exact complementary color of the background (#ABA362). This also directly inspired the rest of the color palette, such as the color of the tables. It was created with Color Wheel, an online tool that uses math to find mathematical color complements and harmonies.

Fragmentation, Superposition, Recombination

Tropicalia championed fragmentation, superposition and recombination of elements as an anthropophagous practice, and this has remained even in modern Brazilian design (Cardoso 2005, p. 237-239). Using surrealistic elements, they created agglomerated compositions. Due to the overlapping of elements, there was sometimes a difficulty in distinguishing the background from the figures (Zan 2009, p.07). This is the direct inspiration for the large screen version of the initial animation, creating a super-imposed, barely readable conglomeration of letters.

The idea of superposition is clearly visible in items from the era and those influenced by it. The cover of the album “Technicolor”by Os Mutantes is a good example of Tropicalist influence. This was the inspiration for the utilization of making the magazine title (h1) see-through, so that the colorful background was exposed.

The way the see-through background title was applied was the following:

h1 {

background: url("../../img/bg/tropicalia/tropheader.jpg");

-webkit-background-clip: text;

-webkit-text-fill-color: transparent;

-webkit-background-clip: text;

-moz-background-clip: text;

background-clip: text;

}

Layout & Symmetry

There are no formal rules about the layout of Tropicalist-influenced design, as most of the objects created in its influenced are not text-heavy. While the movement had a strong desire to break with the functionalist aesthetics of the 1960s (Tafarelo de Oliveira 2011), it also strongly ingested the concept of symmetrical layouts, as part of Ulm School of Design trends as well as Bauhus influences (Espinosa 2018, Tafarelo de Oliveira 2011). This was the main inspiration for making the text justified and two-columned (on larger than 812px screens).

The layout of the main article was structured as follows:

main p {

text-align: justify;

}

figure > figcaption {

text-align: justify;

}

main {

-webkit-column-count: 1;

-moz-column-count: 1;

column-count: 1;

column-gap: 5vw;

}

main {

-webkit-column-count: 2;

-moz-column-count: 2;

column-count: 2;

column-gap: 7.5vw;

}

THEME BACKGROUND IMAGE: Llew Mejia - Illustrator/Surface Designer - www.llewmejia.com

Cardoso, Rafael. “Uma Introdução à História do Design.” Rio de Janeiro: 3ª Edição, Edgar Blucher, 2008.

Cuzner, Dave. “Rogerio Duarte and the Tropicalia Movement.” Grain Edit, Grain Edit, 23 June 2010.

Espinosa, Natalie. “Rogério Duarte, Design and Tropicália.” Dream Box, Dream Box, 29 Aug. 2018, www.dreambox.nyc/blogposts/2018/8/24/rogerio-duarte-design-and-tropicalia.

Longo, Matheus. “O Encontro Impulsionador Da Tropicália Com o Design Gráfico No Brasil.” Folks, Medium, 4 Nov. 2016.

Lotufo E. “Cor e comunicação”. Universidade católica de Goiás, Departamento de Artes e Arquitectura, curso de design, Goiânia. 2008.

Rodrigues, Jorge Caê. “O design tropicalista de Rogério Duarte.” In: MELO, Chico Homem de. (Org.). O design gráfico brasileiro anos 60. São Paulo: 2ª Edição, Cosac Naify, 2008.

Tafarelo de Oliveira, Cauhana. “A Ruptura Tropicalista No Design Grafico.” Repositorio Roca UTFPR, Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná, Departamento Academico de Desenho Industrial, 2 July 2011.